Managing director, hunter, and founder at Ravnø.

The year is 1979, the dry season has arrived in the eastern Kalahari. We are southeast of Tshane, the outpost that houses a few people and a small shop that also sells petrol – and a monastery. I am with my father, who is on his rounds. As the RMO (Regional Medical Officer), this is part of his responsibility. Since the early seventies, my father had been responsible for half the country. There weren’t many doctors in Botswana from 1966 when Bechuanaland ceased to exist until the beginning of the eighties.

Mostly, it involved basic medical treatment, training, and further education of missionaries who would be able to carry out vaccination programs and contribute knowledge about family planning – as well as providing simple healthcare services.

This particular year is different. The recent drought has led to a shortage of water, and many of the wild animals that used to inhabit the surrounding areas have migrated north in search of water. This was the first major drought – the first of six consecutive droughts that eventually led to Live Aid for Ethiopia in North Africa.

I remember vividly when we arrived at the shop – the owner was glad to see my father again, and there was a long queue of people with various ailments seeking help. But first and foremost, there was a problem that needed to be solved. The outpost’s only water source was a wind-powered water pump a kilometer away. Local girls would walk back and forth, several times a day, to fetch water that they carried home in buckets balanced on their heads. A pride of lions with three young cubs and two adult lionesses had taken residence around the water pump. These same animals had also taken some cattle and goats.

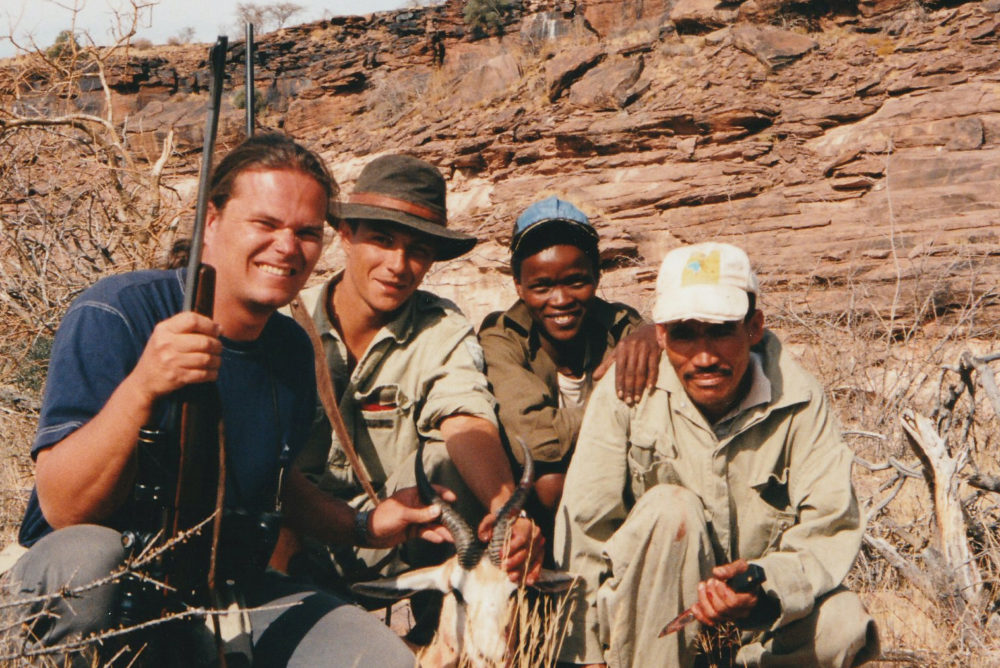

The shop owner knew that my father always carried a rifle when he was on long rounds in the Kalahari and Okavango. Most of the time, it was for hunting small dik-dik antelopes, guinea fowl – or occasionally a springbok. The meat was a good way to connect with the local San people, nomadic hunters who rarely stayed in one place long enough to conduct a vaccination campaign.

According to the local San hunters, the challenge was that these lions had little life experience – they hadn’t followed the wild animals that had migrated out of the area. Now there were few alternatives for what to do with them. After some discussion, the local hunters and my father concluded that the best course of action would be to shoot the three youngest lions so that the older lionesses could leave the area.

The hunt began at five in the morning the next day. Watching a San hunter track an animal in the Kalahari is something in itself. In the first part of the day, he sat balancing on the roof of an older Ford F250, using a stick as a pointer for the driver. We drove for several hours – or at least it felt that way. I noticed that we had entered an area with denser bushes. Finally, he gently tapped the roof. The car stopped. He climbed down and explained that the animals had split up; we had a lioness with two cubs in front of us, maybe only a few hundred meters away.

My father stepped out of the car with me in tow. Two Rhodesian Ridgeback dogs were let out of the car. They quickly found the track and took off.

It didn’t take many minutes before we could hear lion roars and barking intertwined. The San hunter and a dog handler led the way. My father, with his Remington 30-06, was in front, and I followed behind. Throughout the journey through the bushes, we could hear the dogs. The hunter who was tracking and leading the way was most concerned about the wind direction but also kepta close eye out for a possible ambush from the other animals. It felt like an eternity. I could see that my father was calm, so I didn’t feel any fear. The San hunter crouched down quietly and pointed. There, just 50 meters ahead of us, were both dogs and one of the young lions. One dog was in front, guiding, while the other bit the lion’s tail. When the lion turned, the roles of the dogs switched. My father quickly moved forward, dropped to his knees, aimed… and shot.

I didn’t quite understand what was happening, but the San hunter was quickly on his feet, running forward. He shouted and made clicking sounds. The dog handler shouted at the dogs. Now I realized that the animal we were after was there. Similar to hunting dogs here at home, live animals are more exciting than dead ones. Both dogs darted away, despite vigorous calling. Just as I reached the spot where the shot was fired, a new chase began a few hundred meters away.

There wasn’t much time to stand and admire the kill. This young “problem lion” had to pay with its life too soon, but sometimes that’s what it takes to save others. We heard the car moving through the bushes, and I was told to stay where I was with the dog handler while my father and his tracker went after the other lion. The car was only a hundred meters away. A few minutes later, we heard a series of shots. We loaded the first animal onto the flatbed of the car and drove through the thorn bushes to where we heard the shots coming from. When we arrived, the San hunter was already busy skinning one of the two young lions. They had managed to catch both remaining animals that we were supposed to take out. There was wild jubilation. The driver, my father, the dog handler, and the San hunter slapped each other on the back, smiled, and sang. My father had a wide grin on his face. “Yes, now you’ve been on a hunt,” he said to me. I almost burst with pride. I hadn’t shot anything, but I had been on a lion hunt!

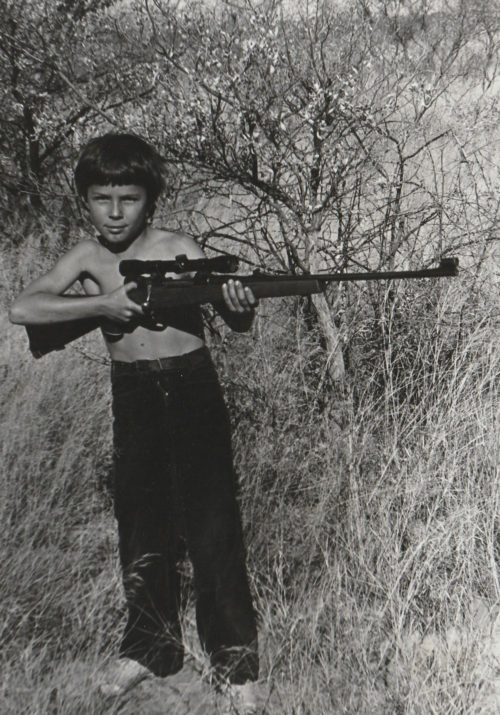

That’s where it all began. I was only 8 years old, but from that point on, I had a childhood immersed in hunting among hunters. Little did I know at the time that I had found what would mean the most to me in life as a hobby – and eventually as a job. Ravnø is, in many ways, an extension of my interest in hunting. I have always enjoyed the company of other hunters.

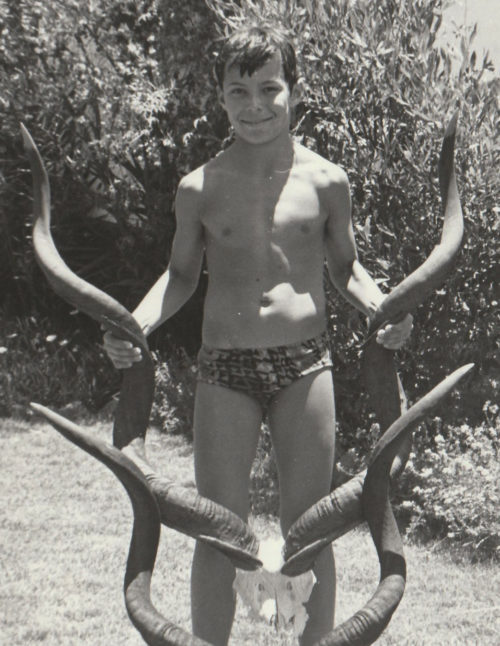

I was fortunate – this was in the time before game farms and hunting tourism exploded in Africa. It was simply a matter of buying a hunting permit for a specific area and setting off. In the years following my debut, I got to hunt kudu, gemsbok, springbok, and many other wild animals of Africa. The books by Robert C Ruark, Ernest Hemingway, Theodore and Kermit Roosevelt, and Peter Hathaway Capstick were on the nightstand as bedtime reading.

Mostly, it was hunting for meat since my father wasn’t very concerned about preserving the horns or hides. A bit unfortunate, actually; the kudu we shot in 1985 would have been a record-breaking animal to this day. It was shot in the North Kalahari, with horn length over 70 inches. A remarkably large animal.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, I started making more trips to my homeland, the Czech Republic. I got a taste for wild boar hunting early on, and my visits to Africa became less frequent. There were a few trips, and some guiding work.

It’s difficult to look back now. I believe Africa has changed so much since I lived there that I’m afraid of ruining my childhood memories. Central Asia is the most tempting destination these days – and perhaps one day Canada or New Zealand.

Isack was a genuine San “Bushman” from the Kalahari and the best at finding what we were after.